A Whole New Fold

By Anton Willis, CDO Warning: this post is nerdy and gets into lots of detail about how we design foldable kayaks.

By Anton Willis, CDO

Warning: this post is nerdy and gets into lots of detail about how we design foldable kayaks. But we still think it’s pretty interesting! If you’re looking for awesome adventure photos with mountains and dogs and stuff, click here.

I laughed out loud the first time the idea that would become the inlet was thrown at me. Ardy, after an outing to Lake Merrit with friends in his 1970’s two-door beamer, said it first: “Could we make a kayak box small enough to fit two in a car trunk?” I shook my head and returned to work. I mean, we’d already made a 16 foot kayak fold down into the size of an (admittedly big) suitcase. What more did he want?

But things like that tend to stick with me. In our very early days, if I was struggling with a design problem, Ardy would tell me, “I don’t think it will work that way”- which was his way of motivating me to prove him wrong. It often worked. We had set out to make truly innovative kayaks, and I took that challenge seriously.

So in 2019, when we started spitballing the project that would become the Inlet, I remembered that conversation. We’d wanted to make a truly affordable folding kayak since we started the company, but the pressing realities of bandwidth and manufacturing costs had always nipped it in the bud. Now, we finally felt ready. And I was ready to start folding from scratch.

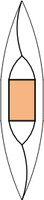

All of the other Oru Kayak models follow the same basic DNA- the ends accordion inwards toward the center of the kayak, with five folds in the 12 foot models and seven in the 16 foot models. The middle section of the kayak becomes the box. The two accordioned ends slide past each other when folded up (you can see it in action here)

The first design decision for the Inlet was to make it fold in thirds, rather than fifths. This would avoid the accordioned ends, making assembly easier, and allowing the ends of the kayaks to remain permanently closed. We’d settled on a 10 foot length for the boat- divided in thirds, this led to a box length of around 40 inches. The good news was that this fit well within the well-to-well width of most car trunks.

The bad news was that the side-by-side folding motion of the other kayaks didn’t work well in the new box shape. This was when we really had to go back to the drawing board (or in this case, the folding table), and rethink the basic DNA of our folding system for the first time in 10 years.

People often ask “what 3d modelling software do you use for the kayaks?”. The answer is none (although we do use Fusion 360 for smaller parts). We use dozens of paper and cardboard models to work out the fold patterns and kayak shapes. Origami is not just a metaphor for how our kayaks fold- it is how they work, and literally how they are designed.

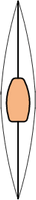

While playing with one paper model, I forced the folded front kayak over the folded back, instead of side by side. It didn’t really work; the folds didn’t line up right, and it ended up crumpled. But it was close enough to seem promising.

The key to making the new design work would be nesting all of the internal geometries perfectly, so that everything would fit into the box with minimal wasted space. This would need a level of rigor and perfection we hadn’t used in other models. The other problem was that we couldn’t see inside the cardboard models to see how the folds were really fitting together. In semi-desperation, I cut a model in half to take measurements, and quickly realized that if the cardboard models were designed as independent halves, we could see inside, and adjust the two halves independently.

After a few rounds, we got something that worked in cardboard. Time to go full scale! For this, we have a fun prototyping machine that can cut and make fold lines for any pattern we draw.

It worked! We had a functioning 10 foot kayak that weighed 20 pounds, and took just minutes to assemble. And best of all, you could fit two (or even three!) in a car trunk. Sometimes we amaze even ourselves. Of course, getting all the details right would take several more months. But there was one bigger problem we’d never dealt with before…

The new fold pattern had a few lines that were very difficult to fold, and we were committed to making the Inlet as easy to use as possible. This wasn’t a problem that could be solved with cardboard models- to fix this, we’d have to change the material itself.

We get our skin material custom-made, from a few different factories. It’s an extremely tough, durable twin-walled polypropylene, which can be folded 20,000 times without breaking. The problem was that we’d engineered it to work on boats like the Coast XT- 16 feet long and capable of paddling in the open ocean, it needs to be as rigid as possible. For the Inlet, we needed something more flexible- but still equally resistant to folds, impacts and punctures. Solving this problem took many calls with factory engineers, and extensive testing of samples and full sized kayaks. We built a custom testing machine to measure bending strength, and also relied on more primitive methods- simply folding kayaks hundreds of times, and having beta testers give extensive feedback on assembly. This too took several tries to get right.